April 20, 2012

Editor’s note: In the first installment of this three part series you got a postcard journey, of impressions in a telegram. In this second part, stay a little. Experience some of the sessions through song as the author Vipul Rikhi does. This edition explores the power of ‘bhajan’ singing .Songs of depth, songs of life, where the conversations get more meaningful and the deepening more joyful. Ananda doesn’t come with the dead weight of gravitas clearly. But what does it come with? Read on

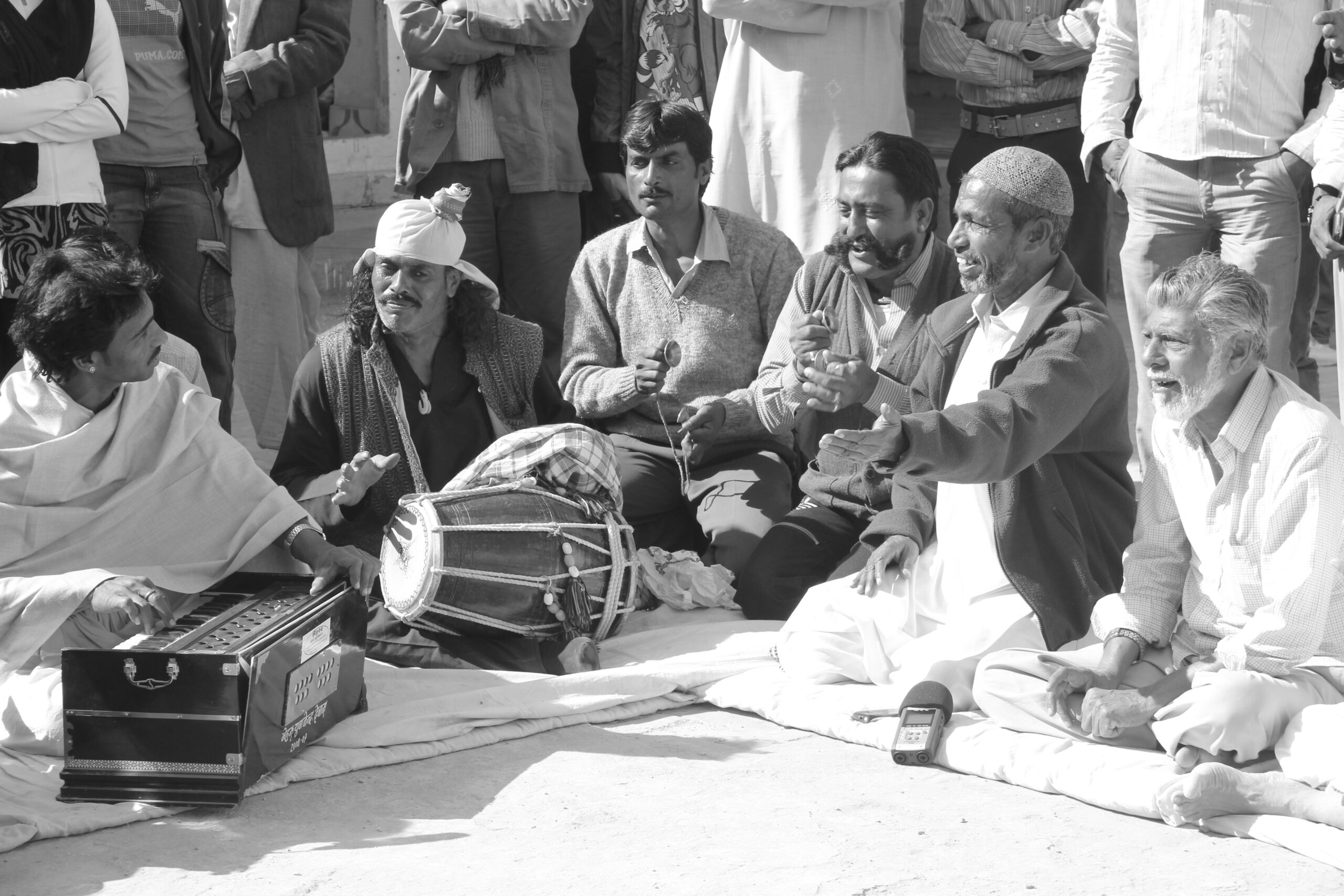

The tradition of bhajan goes back a long way in India. It is a form of ‘smaran’, remembrance, and ‘jap’, repeated mental or verbal utterance, another name for remembrance. All of it refers to remembering — but remembering what? In spiritual traditions it points to a constant remembrance of the Word, the Name or, if you like, the Source.

But bhajan has another purpose or function — that is, to strike home a truth; to wound (‘chot pahunchana’); and often, just one strike is enough. This one-time strike, this wound, should then itself needle you into constant remembrance. The Rajasthan Kabir Yatra, organised in villages around Bikaner in February 2012, carried many such wounds — at different times and places for different people — administered through the innocuous-looking vehicles of music and poetry.

If the wound is deep, so will the cry for help be. Abdullahbhai, one of our co-yatris, pointed to this when he elaborated on the fate of lovers. He and his companion Musa Para, both from Kutch, were singing Sufi songs for us, and Abdullahbhai explained the words and their import. The very first song, by Sahib Dinna Shah, turned out to be an argument with God. Creation arose when the Creator first fell in love, said Abdullahbhai. Love is the foundation. And the Creator is the original lover, the first aashiq, in love with his creation. But how does this creation, this world, actually treat people who fall in love? The poet disputes with God — Do you call yourself a lover? Look, how you deal with those who love! Sasui (a folk heroine), in search for her beloved Punnu, died a miserable death in barrenness the salt desert, trying to cross the Rann of Kutch. And you who are supposed to be a loving creator, you dare to call yourself a lover? Look, what happened to Ranjha. He went from a life of ease to being a cowherd and then a wandering yogi before he too died unlamented. And what was his crime? He fell in love because you appeared in the beautiful guise of Heer. Consider the fate of Qais, who got labelled Majnu, the Mad One, crazy for his Laila, and died likewise in the desert. Do you then call yourself a lover? And leave alone these earthly lovers, what of Husain, who died in Karbala trying to defend your faith? And still you call yourself a lover?

Not for nothing is it said, Abdullahbhai remarked, that he who loves can forget about a good night’s sleep ever — his sleep and happiness are gone forever! Not so easy to live in forgetfulness once you are awake. And what else does it mean to fall in love — to finally come alive, to awaken?

Another clear moment of being struck came for me on a bus-ride. It seemed a harmless enough one. Kaluram Bamaniya, from Malwa in MP, was singing for us during a bus journey from Bikaner to Pugal. He sang a few Meera bhajans, the most enchanting of which was ‘Nath mhari dai do, ho Girdhari’. We

were all quite taken by it — such a sweet, simple melody it seemed to be. The first two lines run like this: (Return my nose-ring to me, O Krishna / My moon-like face is barren without it.) Innocently someone asked him what this nose-ring stood for. None of us was quite prepared for the answer.

‘Sadhu ki kamai uske chehre pe hoti hai,’ replied Kaluram in explanation (A seeker’s true earnings are reflected on his visage). The conceptual leap from Meera asking for her nose-ring to a seeker’s true earnings was unexpected and breathtaking. Suddenly it all made sense: what the nath signified, and the true meaning of how it lights up the face (‘chehre ka noor,’ as Kaluram put it)

A more delightful vein of being struck was on first hearing Bindhumalini from Chennai singing a previously-unheard Kabir bhajan (she found it by chance in some obscure tome in Kolkata) set to music by herself. A happy, flowing, rocking composition! And the words flowed, too.

‘Naache re mero mann nato / Gyan ke dhol bajaye rain din, rain din’. It was refreshing to hear talk of gyan (knowledge, wisdom) in such a light, lilting vein. The thrust of the song is something like this: My heart, the dancer, is dancing unstoppably, beating the drums of wisdom, night and day, night and day; and all the planets are dancing to its tune, and even the Creator cannot resist joining in this dance!’

And if even the Creator couldn’t resist, then who were we to do so? So many of us jumped up and danced with abandon and joy. The image that’s struck in my head, though, is that of ‘gyan ke dhol’ (the drums of wisdom). What a joyful way to say that wisdom when it arrives makes one sing and dance,

rather than sink deeper into the pages of a scripture!

After all the various wounds gathered through the yatra like pearls from the sea-floor, a kind of balm was put by Parvathy Baul on the final evening in Bikaner, when she sang a song she’d recently learnt from Prahlad Tipaniya of Malwa. So here was a Baul singer from Trivandrum, singing a Malwi folk-tune while swirling and dancing in her mad Baul way (the root of the term Baul goes to madness, or what the normal world considers madness). The whole audience was charmed.

She sang it so sweetly, as a show of gratitude to Prahladji, for teaching her. ‘Tu pee le amiras dhara, gagan mein jhadi lagi’ (Come, drink deep of this nectar-gush, which is streaming across the sky…). I can almost feel the nectar soothing my soul whenever I enter deep into this song. The bhajan ends appropriately by saying, ‘Kabir sangat mein ho hamari, daali prem ki hari-bhari’ (In Kabir’s good company, the branch of my love is green and blossoming).

When the last song of the yatra had been sung, at the beautiful new amphitheatre of the Dharam Sajjan Trust in Bikaner, a local man caught hold of me and started asking me about Parvathy and the meaning of her songs. I had no words to explain anything. But the man went on himself — one could see that he was moved; something had been touched, perhaps even struck. ‘Sab bhaavon ka khel hai,’ he repeated several times (it’s all a play of feelings). He kept saying it, as though that sentence captured everything that he was feeling. Perhaps he meant that these songs, the bhajans, and their performance in music, evokes certain feelings which are the very stuff of life, and which are experienced more fully and purely in the listening, away from our everyday short-circuiting of emotions in the business and tension of ‘normal life’. ‘Dhan ki bhi baat nahin hai,’ (even money does not come close), he said, to express fully the importance of what he had formulated.

Feelings, only feelings. But which ones? The feeling of chot, the wound, of being struck? Feeling helpless, open, ready to receive?

Read Yahoo News Post here